Penokee Hills Mine Could Devastate Environment, Local Economies

Andy Davis

adavi481@uwsp.edu

On Tuesday, Feb. 28, Frank Koehn held a presentation in the DUC Theatre to educate people about the destructive nature of the Penokee Hills iron mine proposal.

“This is a resource war,” Koehn began. “It’s about the water.”

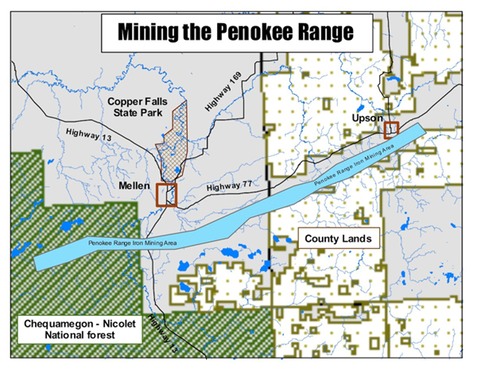

The area where the proposed iron mine would be placed—which covers a 22-mile, 22,000-acre strip of the Penokee Hills from southwest of Hurley to west of Mellen—contains 71 miles of rivers and streams. Many of these waterways empty into the Bad River and eventually find their way to Lake Superior, contamination of which could be catastrophic. “All waste products will end up in the Bad River,” Koehn warned.

A pamphlet distributed at the presentation states the contamination of Lake Superior could prove detrimental to the economies of lakeside communities such as Bayfield, Washburn and Ashland. Native American tribes such as the Ojibwe and the Anishinaabeg of Bad River would also suffer greatly.

The Nature Conservancy has dedicated a page on its website to this issue. It explains that “these waterways—including the Bad, Potato and Tyler Forks rivers—are designated as Exceptional or Outstanding Resource waters, meaning they are among the highest quality rivers in Wisconsin, having good water quality … and supporting valuable fisheries and wildlife habitat.”

Gogebic Taconite has proposed extracting iron ore from the Penokee-Gogebic Range, which extends 25 miles through Iron and Ashland counties in Northern Wisconsin.Graphic courtesy of headwatersnews.net

Glenn Wills, an attendant of the presentation, said, “I just think it’s more than obvious that the jobs that the mining bill will supposedly create are going to be far less that the jobs that are currently provided by the job structure of the area surrounding the mine.” He said that these small businesses, including rice fields and fisheries, would be better off left as they are. Currently there are around 1,000 jobs, and Wills concluded, “This is going to be less than 1,000 and it’s only going to be for five years.”

An acquaintance of Wills, Brett Deutscher, wondered out loud after the presentation how many people around the proposed mine site would actually be able to work the jobs generated. He asked what percentage of unemployed people were single mothers or were in other situations that prevented them from working at the mine.

What is difficult to understand is why so much environmental degradation is necessary for so little iron. Koehn explained that the mineral sought after by mining companies is not raw iron ore, but rather taconite. Taconite in an iron formation and occurs as streaks in the Penokee Hills. Iron is found in this taconite as magnetite, an iron oxide that is only between 25 and 30 percent iron. Koehn said that this iron is low quality and will most likely be shipped overseas to countries like India and China.

The out-of-state companies RGGS Land and Minerals, Ltd. of Houston, TX, and LaPointe Mining Co. of Minnesota own much of the land that will be utilized for mining purposes. The Cline Group of FL also has a claim on the property’s mineral rights, and in order to move forward with iron mining has organized the subsidiary Gogebic Taconite (G-TAC).

According to the Ashland Current, a report was released last April by NorthStar Economics that claimed the Penokee Mine would generate 700 permanent jobs and about 3,000 temporary jobs. Bad River attorney Glenn Stoddard, however, says the report was biased because G-TAC paid for the study.

Further frustration derives from the legislative promotion of these potentially devastating environmental effects. Assembly Bill 426—introduced to the Wisconsin state legislature on Dec. 14 of last year by the Committee on Jobs, Economy and Small Business—is intended to loosen regulation on mining practices. In the overview section at the beginning of the proposal, it is written:

“Under current law, the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) regulates mining for metallic minerals. The laws under which DNR regulates metallic mining apply to mining for ferrous minerals (iron) and mining for nonferrous minerals, such as copper or zinc.

This Bill [AB-429] creates new statutes for regulating iron mining and modifies the current laws regulating metallic mining so that they cover only mining for nonferrous minerals.”

Koehn summarized some of the most striking details of the bill. He said that the bill would relax regulations on mining practices. For example, under the bill the DNR would not be allowed to monitor the 815 acres of Iron County that will be set aside for the waste generated by this mine.

He also said that mining would be allowed in wetlands and waterways, areas where mining is generally restricted. This bill “allows mining law to supersede all other environmental regulations,” Koehn said.

At the conclusion of the presentation, Koehn urged the audience to call legislators often and make it known that this mine should not be dug. He also promoted his activist website, savethewatersedge.com, and mentioned that visits to the Penokee area are being planned for mid-March and early April.

University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point

2100 Main Street Stevens Point, WI 54481-3897 • Phone: 715-346-2249

Direct comments to pointer@uwsp.edu