SEIZING INDIAN LANDS

Tribal leaders, environmentalists and local officials have united to fight a massive mine which could be toxic to a water-rich area known as “Wisconsin’s Everglades.”

By Al Gedicks - Apr 16th, 2013 11:21 am

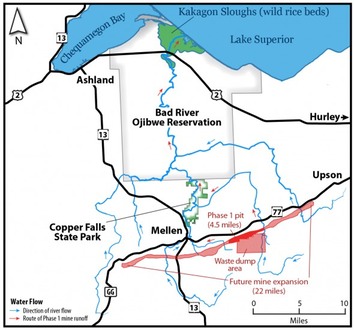

A view of the waterways and Bad River Ojibwe Reservation impacted by the proposed mine. Map by Carl Sack, Wisconsin Network for Peace and Justice.

In the mid-1820s, preceding the outbreak of the Black Hawk War, thousands of lead miners invaded Indian communities in southwestern Wisconsin and seized the lead mines and the indigenous knowledge of the mining process from the Sauk, Mesquakie and Winnebago people. The Winnebago Revolt of 1827 and the Black Hawk War in 1832 was a response to this resource theft. “By the mid-1830s,” notes the late University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire treaty historian Ronald Satz, “removal treaties had opened large portions of southern Wisconsin to white settlement, and American policymakers cast covetous eyes on Chippewa lands in the northern part of the state.”

By the time of one of the first treaties between the United States and the Ojibwe (Chippewa), made at Fond du Lac in 1826, Henry Schoolcraft, the famous geologist-explorer, had confirmed the existence of rich copper and iron deposits along the shores of Lake Superior. The 1842 “Miners Treaty” of La Pointe dispossessed the Ojibwe of the Keeweenaw copper districts. The western boundary of this treaty was first drawn at the Montreal River, Michigan’s border with Wisconsin. But when Michigan’s Indian superintendent, Robert Stuart, learned that the copper veins extended even further west, he urged the government to include almost all Ojibwe lands along Lake Superior. The “main importance” of the Wisconsin territory, according to Stuart, “is owing to its supposed great mineral productiveness.”

Ultimately, Lake Superior Ojibwe leaders had to sign treaties giving up their ownership of lands including the rich copper deposits of the Keweenaw copper districts of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and the extensive iron deposits of Minnesota’s Mesabi Iron Range to the United States. The Ojibwe, however, retained the right to continue hunting, fishing and gathering in ceded lands. These rights were not given to the Ojibwe, but have always been retained by them: Treaty rights are property rights, rights that were never sold and that are common to all property owners. After a federal court decision (Voigt) recognized Ojibwe treaty rights in 1983, white sportsmen held sometimes-violent protests against Ojibwe off-reservation spearfishing.

Anti-treaty groups accused the Ojibwe of destroying the fish and the local tourism economy, even though the tribes never took more than three percent of the fish. Riot police from around the state were deployed at northern lakes during the spring spearfishing seasons to help protect Ojibwe spearers and their families.

Governor Tony Earl issued a proclamation calling for cooperation between the tribes and state agencies after the Voigt Decision. But Earl was defeated in 1986 by Tommy Thompson, who had the support of anti-treaty rights groups like PARR (Protect Americans’ Rights and Resources) and STA (Stop Treaty Abuse). In a campaign speech to PARR, Thompson said, “I believe spearing is wrong, regardless of what treaties, negotiations or federal courts may say.”

At the height of the anti-Indian protests, Thompson sent his top advisor, James Klauser, a former chief lobbyist for Exxon’s proposed Crandon mine, to negotiate a buyout of Ojibwe treaty rights. Exxon, Noranda and other mining companies saw the treaties as obstacles to mining. Klauser was unable to persuade any of the six Ojibwe tribes to “lease” their treaty rights in exchange for money. But it was not the end of attempts to create the Crandon Mine.