Mining Industry Targets “Prove It First” Law

[This article was originally published in Z Magazine, vol. 26 no. 2, February 2013 © Al Gedicks.]

by Al Gedicks

Prior to investing in new resource colonies, multinational mining corporations frequently change a country’s mining laws to remove restrictions on foreign ownership, reduce taxes, ease environmental protections and guarantee access to water supplies needed for mining. During the 1990s, under pressure from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, over 90 states in the Global South changed their mining laws to attract foreign mining investment. These neocolonial measures, often called “neoliberal reforms,” are now being used to open up new mining projects in the Lake Superior region of Wisconsin, Michigan and Minnesota.

Governor Walker presented iron ore mining as viable job creation during his 2013 State of the State address. Photo by Leslie Amsterdam

Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker recently told his supporters in Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce (WMC) that his top legislative priority in the January 2013 session of the legislature is the passage of the controversial Iron Mining bill that was defeated by one vote in the Wisconsin Senate last spring. To advance this agenda the governor has asked Tim Sullivan, his special assistant for business and workforce development, to bring together mining experts from around the world to compare Wisconsin’s mining regulatory framework with other states. Sullivan is chair of the Wisconsin Mining Association (WMA), a past director of the National Mining Association, and a former president, CEO, and director of Bucyrus International, the largest mining machinery company in the world, now owned by Caterpillar Corporation.

WMA hired Behre Dolbear, a global mining consulting firm that specializes in drafting mining laws to suit their corporate clients and “challenging” countries who are perceived to be hostile to the mining industry to change their policies. In their report they criticize the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) for allowing “public participation in technical meetings between the mining company and the WDNR prior to issuance of the EIS [environmental impact statement]. This has led to the process delay, uninformed debates and the process grinding to a halt.” In other words, the problem is too much democracy and transparency in the mine permitting process.

The bill was written by lobbyists for Gogebic Taconite (GTac), part of the Cline Group, run by coal magnate Christopher Cline, who wants to extract low grade iron ore (taconite) from the Bad River watershed near Lake Superior. The entire rationale for separate legislation for proposed iron mining is based upon the misconception that iron mining is different from metallic sulfide mining and that therefore the existing sulfide mining laws do not apply to GTac. According to Sullivan, “We’re talking about digging a ditch, taking the iron ore, filling the ditch in. That’s as simple as what it is.”

The bill was written by lobbyists for Gogebic Taconite (GTac), part of the Cline Group, run by coal magnate Christopher Cline, who wants to extract low grade iron ore (taconite) from the Bad River watershed near Lake Superior. The entire rationale for separate legislation for proposed iron mining is based upon the misconception that iron mining is different from metallic sulfide mining and that therefore the existing sulfide mining laws do not apply to GTac. According to Sullivan, “We’re talking about digging a ditch, taking the iron ore, filling the ditch in. That’s as simple as what it is.”

Not so simple. While the iron ore does not contain sulfides, there is a sulfide-bearing layer of rocks immediately above the iron formation that would have to be removed in order to get at the iron ore. The major problem is that the sulfides in the waste rock can react with water and oxygen to produce sulfuric acid and release heavy metals like arsenic, lead and mercury into surface and groundwaters. This is called Acid Mine Drainage (AMD). Because of the enormous volume of waste rock that would be produced from this proposed mine, even a small amount of sulfide minerals could produce large volumes of acid mine drainage and toxic leachate. Independent geologists provided testimony to the Wisconsin Joint Committee on Finance that just one cubic kilometer of the waste rock containing sulfide minerals could contain the equivalent of 10 billion gallons of sulfuric acid of car battery strength.

The bill contains widespread exemptions from existing environmental regulations, severely limits public and tribal participation in the mine permitting process and ignores Ojibwe treaty rights on the lands sold to the U.S. in the 19th century. The giant open pit mine that would discharge pollutants into the Bad River Ojibwe Tribe’s sacred wild rice beds would be the largest mine in state history. It is only one of several mining projects proposed in the Lake Superior region (see“Resisting Resource Colonialism in the Lake Superior Region,” Z Magazine, September 2011).

Aquila Resources, a Canadian mining exploration company, thinks they’ve struck gold in Wisconsin and Michigan. The company identified gold, copper and zinc deposits in Marathon, Taylor and Oneida Counties in northern Wisconsin and in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula but encountered strong local opposition in both states.

After three hours of well-informed citizen and tribal testimony against the proposed Lynne mine last summer, the Oneida County Board voted 12-9 to discontinue any further mining exploration. Tom Maulson, Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe Tribal Chair, testified that, “Whatever it’s going to take, wherever we have to go, whatever judicial system it’s going to take to stop mining, we’ll pursue it until we have good, clear, convincing evidence that it’ll be environmentally safe mining…Until then, gah-ween (no), can’t happen. We won’t let it happen.”

Opposition to the Lynne mine goes back to the 1990s when Noranda Minerals of Canada announced plans to construct an open pit mine to extract zinc, lead and silver in a wetland area just half a mile from important walleye spawning areas of the Willow River. Even though the area was one of the hotbeds of militancy against Ojibwe spearfishing, local environmentalists built a working relationship with the Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe. Sportsmen also joined the mining opposition, to protect the rich fishing and hunting grounds around the Willow Flowage. The unexpectedly strong opposition, combined with questions about the mine’s potential damage to wetlands, convinced Noranda to withdraw in 1993.

Opposition to the Lynne mine goes back to the 1990s when Noranda Minerals of Canada announced plans to construct an open pit mine to extract zinc, lead and silver in a wetland area just half a mile from important walleye spawning areas of the Willow River. Even though the area was one of the hotbeds of militancy against Ojibwe spearfishing, local environmentalists built a working relationship with the Lac du Flambeau Ojibwe. Sportsmen also joined the mining opposition, to protect the rich fishing and hunting grounds around the Willow Flowage. The unexpectedly strong opposition, combined with questions about the mine’s potential damage to wetlands, convinced Noranda to withdraw in 1993.

Meanwhile, in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, local citizens in Menominee County organized the “Front 40” group in 2003 in response to Aquila’s “Back Forty” proposed gold mine to be constructed almost directly under the Menominee River. The mine could severely pollute both Wisconsin and Michigan waters. Front 40 members, with support from their local government, have challenged mining executives to show how mining could be done without adversely affecting rivers, lakes and groundwater. Subsequent to mounting opposition, Aquila’s joint venture partner, Hudbay Minerals of Canada, withdrew from the project in July 2012. The project is on hold while Aquila seeks new financing for the project.

PolyMet’s Metallic Sulfide Mine

In addition to the iron mining on Minnesota’s Mesabi Range, there are large but generally lean copper-nickel sulfide deposits at the east end of the range that would create over 99 percent waste. Three large copper-nickel sulfide projects are in the development stage. The most advanced project is PolyMet’s NorthMet open pit copper-nickel sulfide strip mine on public land in the Superior National Forest, south of Babbitt. PolyMet is a Canadian company with no mining experience. The Swiss multinational, Glencore, which just acquired the Xstrata mining company, owns or has options on up to 36 percent of the Minnesota company. The new company, Glencore Xstrata International, is now the fourth largest diversified mining company in the world with a market value of nearly $90 billion.

PolyMet recently hired Jon Cherry as their new president and CEO. Prior to this, Cherry managed one of the most controversial mining projects in the region: Rio Tinto’s Kennecott Eagle nickel-copper project in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The entryway to the mine is at Eagle Rock or Migi ziiwasin, a sacred site for the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC). Members of KBIC and their non-native supporters occupied the site after the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality ruled that only buildings may be considered “places of worship” and awarded Kennecott’s mining permit in 2010. KBIC has appealed to the United Nations because the Eagle mine, under construction, poses a threat to the cultural and natural resource rights of the tribe, including the devastation of a sacred place. PolyMet faces similar issues in Minnesota.

The U.S. Forest Service owns the land but PolyMet owns the mineral rights beneath the surface. The USFS does not allow strip mines on federal land within the Superior National Forest where the NorthMet mine would be located. In order for the project to go ahead without requiring current federal protections to taxpayers, the environment or tribal rights, U.S. Representative Chip Cravaack (R-MN) introduced legislation (HR 5544)—which passed the House in October—that would transfer tens of thousands of acres of protected National Forest lands into state management so that the lands could be intensively logged and stripmined for the benefit of multinational mining corporations.

If this exchange is allowed, it would directly affect the reserved property rights of the three Ojibwe bands to hunt, fish and use the land that was sold to the United States in the 1854 Treaty. None of the Ojibwe bands were consulted about this legislation as required by the treaty and by Executive Orders requiring government to government consultation on issues related to Federal actions.

The environmental injustice of this proposal is not limited to the violation of Ojibwe treaty rights in the Superior National Forest. The lakes and streams downstream from the proposed mine are already impaired due to mercury pollution resulting in fish consumption advisories. In February 2010 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reviewed PolyMet’s draft environmental statement (DEIS) and concluded that the PolyMet mine “will result in unacceptable and long-term water quality impacts, which include exceeding water quality standards, releasing unmitigated wastewater discharges to water bodies [during operation and in the postclosure period], and increasing mercury loadings into the Lake Superior watershed.” The EPA gave the DEIS the lowest possible rating and said the project should not proceed as proposed.

While increased mercury loadings would have disproportionate impacts on Ojibwe communities who rely on fish for subsistence, the EPA found that tribal water quality standards and higher fish consumption rates of the Fond du Lac and Grand Portage Ojibwe bands had not been considered. Receiving waters of the St. Louis River watershed, the largest tributary to Lake Superior, already are believed to be impaired for wild rice due to taconite mining sulfate discharges, but are not yet listed as such by the state. Tribal harvesters of wild rice in the headwaters may also be adversely affected by PolyMet’s sulfate discharges and changes in water levels. A supplemental draft environmental impact statement for PolyMet is scheduled for release in mid-2013.

All of these deposits are located in sulfide ore bodies that have the potential to generate acid mine drainage and contaminate local water supplies. There is already significant mercury contamination in the Lake Superior region from past and present iron and copper mining. High levels of mercury in Lake Superior fish pose a serious health risk to pregnant women and nursing mothers who can pass the mercury to their babies in the womb. Mercury is a neurotoxin that affects the brain, kidneys and nervous system of the developing fetus.

A recent Minnesota Department of Health study looked at mercury levels in newborn babies in Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan. They found that one in 10 infants born on Minnesota’s North Shore had potentially unhealthy levels of mercury in their blood. Researchers suspect that sulfates from sulfide mine wastes accelerate the production of methyl mercury taken up by fish and wildlife, leading to fish consumption advisories. Elevated sulfates also decimate natural wild rice stands.

Wisconsin’s “Prove it First” Law

Weak laws and lax enforcement undermine efforts to protect our water, wildlife and communities from this dangerous form of mining,” according to Michelle Halley, an attorney with the National Wildlife Federation (NWF) and author of its recent study of metallic sulfide mine regulation in the Great Lakes region. “There is an urgent need for the region to address these issues now or likely face decades of contamination and clean-up,” says Halley. The EPA estimates that the headwaters of more than 40 percent of the streams in the western United States are contaminated by pollution from hardrock (copper, gold and other nonfuel minerals) mining. Copper sulfide mines are the largest source of taxpayer liability under the EPA’s Superfund cleanup program.

It was this track record of sulfide mining pollution that prompted a massive grassroots environmental, sportfishing, and tribal movement to successfully oppose Exxon’s metallic sulfide mine at the headwaters of the Wolf River and enact Wisconsin’s landmark Mining Moratorium Law, also known as Wisconsin’s “Prove it First” law in 1998. The legislation was passed by overwhelming bi-partisan margins (27-6 in the Senate and 91-6 in the Assembly). More than 60 organizations supported the legislation along with petitions signed by more than 40,000 citizens.

The law requires that before the state can issue a permit for mining of sulfide ore bodies, prospective miners must first provide an example of where a metallic sulfide mine in the United States or Canada has not polluted surface or groundwater during or after mining. So far, the industry has not been able to find a single example where they have mined without polluting water. The NWF study called Wisconsin’s “Prove it First” regulation an exemplary law.

Unable to mine sulfide ore bodies without polluting water resources (as required by the moratorium) the industry is trying to repeal the law. “We would take the stand that if the moratorium went away, that would be a very significant signal to mining companies,” said Ron Kuehn, a lobbyist for Aquila Resources. Ever since the passage of the law, the international mining industry has ranked Wisconsin among the least attractive places for mining investment.

To change the investment climate, Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce (WMC) and other outside groups paid $2 million in attack ads to defeat Jess King (D-Oshkosh) who had voted against the Iron Mining bill. With new GOP majorities in the Wisconsin Legislature, Governor Scott Walker, along with the Wisconsin Mining Association (WMA) and WMC, has made the repeal of “Prove it First” their top legislative priority in 2013.

Tim Sullivan is leading the attack. He recently told a Wisconsin Senate Mining Committee that Wisconsin’s Mining Moratorium was an obstacle to new sulfide mine proposals. “Today, some of the richest mineral deposits in our country lie buried under Wisconsin and thousands of good jobs are buried there with them,” he said.

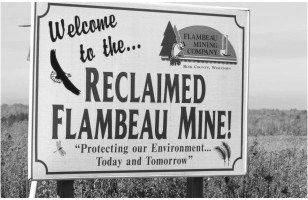

The Flambeau Mine

Mining lobbyists have cited the “success” of the partially-reclaimed Flambeau metallic sulfide mine in Ladysmith, Wisconsin as a major reason for repealing “Prove it First” legislation. “The moratorium says a company has to prove a mine was successfully closed for 10 years, said Aquila’s Ron Kuehn. “Curiously, the best example of that we know of is right here in Wisconsin. That’s our reading of it.”

If the Flambeau mine is the best example the industry can come up with, then this flawed mine is instead a major reason why Wisconsin’s “Prove it First” law needs to remain in place. The Flambeau mine, owned by Kennecott/Rio Tinto, operated for four years and closed in 1997. Reclamation began in 1998 and is still not complete.

In 2007, Flambeau Mining Company (FMC) applied for a Certificate of Completion (COC) for reclamation of the mine. Several environmental organizations, along with the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Tribe, challenged the COC because monitoring at the site demonstrated that the reclamation was not only incomplete but that the site has been polluting nearby Stream C, a tributary of the Flambeau River, for many years. In fact, every water sample collected by either the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) or FMC since 1999 showed concentrations of copper in the mine’s stormwater discharges exceeded the Acute Toxicity Criterion for copper established by the DNR to protect fish and aquatic life.

In 2007, Flambeau Mining Company (FMC) applied for a Certificate of Completion (COC) for reclamation of the mine. Several environmental organizations, along with the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe Tribe, challenged the COC because monitoring at the site demonstrated that the reclamation was not only incomplete but that the site has been polluting nearby Stream C, a tributary of the Flambeau River, for many years. In fact, every water sample collected by either the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) or FMC since 1999 showed concentrations of copper in the mine’s stormwater discharges exceeded the Acute Toxicity Criterion for copper established by the DNR to protect fish and aquatic life.

The company received a partial COC but was denied certification for Stream C where FMC had discharged contaminated runoff from the mine site since 1998. FMC’s subsequent cleanup efforts failed to stop pollution of Stream C. When the DNR refused to cite the company for violations, the Wisconsin Resources Protection Council (WRPC), the Center for Biological Diversity and WRPC member Laura Gauger filed a federal lawsuit against the company. U.S. District Judge Barbara Crabb recently ruled that FMC violated the Clean Water Act on numerous counts. The violations which were proven at trial and subject to penalties occurred between 2007 and 2012. Clear and undisputed evidence shows even more serious violations occurred between 1999 and 2006 but were outside the 5-year statute of limitations.

Under the terms of the Moratorium Law, Flambeau cannot be used as an example mine to meet the law since it is polluting Stream C. The Wisconsin DNR recently completed an investigation of water quality at the mine site and recommended that Stream C be included on its list of “impaired waters” for 2012 for “acute aquatic toxicity” caused by copper and zinc. Earlier this year the DNR issued a report that directly links this pollution to the Flambeau mine.

While the Clean Water Act lawsuit did not address groundwater pollution problems at the Flambeau mine site (the act is specific to surface water quality issues) there is significant groundwater pollution within the backfilled pit about 600 feet from the Flambeau River. Dr. David Chambers and Dr. Kendra Zamzow of the Center for Science in Public Participation in Bozeman, Montana did a study of FMC’s own data from monitoring wells within the backfilled pit. They found manganese levels as high as 42,000 mcg/l. The medical literature reports that consuming water with a manganese level of about 14,000 mcg/l, (only 1/3 of what was found in the monitoring well), correlates with the kind of nerve damage seen in Parkinson’s Disease.

Mining proponents are misleading the legislature and the public by citing Kennecott’s Flambeau Mine as an example of environmentally safe mining. The mining industry has cited the Flambeau mine to justify new metallic sulfide mines in Michigan, Minnesota and Alaska. But groundwater and surface water contamination problems at the Flambeau mine site confirm the need for keeping Wisconsin’s “Prove it First” Law on the books.

If the mining industry can’t help polluting the water at one of the smallest metallic sulfide mines in the state, what can we expect at the larger mines being proposed in the Bad River watershed and on the Menominee River? Why would Wisconsin legislators consider de-regulation of mining when the dangers of metallic sulfide are well known?

Jobs, Jobs, Jobs

Governor Walker told his supporters in the WMC that if the Iron Mining bill were passed in 2013, GTac would “move forward with a mine which would put people to work right off the bat.” Senator Bob Jauch (D-Poplar), whose district encompasses the proposed mine, said the governor is “delusional” if he believes what he told business leaders about potential changes in the state’s mining laws. “The governor is doing an extreme disservice to the people of Wisconsin by suggesting that somehow there is going to be construction activity and the creation of many jobs in the year 2013 if we pass this legislation.”

Jauch explained that even if the Iron Mining bill passes, it would take the company at least two years to get a permit to begin construction. Even if they obtained a permit, mine construction is highly unlikely given the slowdown in Chinese demand for steel. Iron ore prices plunged from $150/ton in April to $87 in September 2012. Cliffs Natural Resources, the nation’s largest producer of iron ore pellets, is laying off 125 workers at Northshore Mining in Minnesota and 500 workers at its Empire Mine in Michigan due to falling iron ore prices.

All the promises about mining jobs do not take into account the extreme volatility of metal prices and the long-term trend toward automated mining. Such promises also ignore and devalue all the existing jobs and ways of life that depend upon clean water that will be threatened by massive mining pollution.

If there is no immediate prospect for mining jobs, what is the rush to pass a mining bill that will completely gut Wisconsin’s regulatory framework for mining and exclude the public and tribal governments from the decision-making process? The larger political agenda of the mining industry is to get rid of Wisconsin’s “Prove it First” Law which is increasingly being seen as a model for metallic sulfide regulation in Minnesota, Michigan and wherever new sulfide mines are being contested by local communities. The mining industry does not want to have to defend its abysmal track record of metallic sulfide mining.

Don’t expect Wisconsin citizens and tribes to allow the repeal of the Mining Moratorium without a fight. A major demonstration at the state capitol to defend the Mining Moratorium has been called for January 26 when the legislature reconvenes.

A sign-on letter to Wisconsin legislators and the governor urging rejection of the Iron Mining bill and repeal of “Prove it First” is available here at the Sierra Club’s website.

[Al Gedicks is professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and Executive Secretary of the Wisconsin Resources Protection Council. He is the author of Resource Rebels: Native Challenges to Mining and Oil Corporations, South End Press, 2001. Check out Gedicks interview on WORT.]