If mining companies have their way, northern Wisconsin may see a massive, twenty-one mile long open pit iron mine developed within the next ten years.

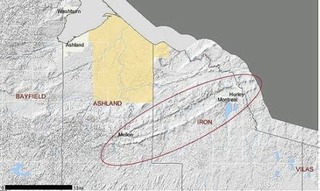

The minerals in question are situated in the Penokee-Gogebic Iron Range, which runs southwest from the western Upper Peninsula of Michigan to southeast Bayfield County, Wisconsin.

Location of Iron Deposit

Called “Penokee” by some and “Gogebic” by others, this scenic line of hills has a long and storied mining history. The first official record of iron in the area was included in an 1848 report by Dr. A. Randall on iron ore he found between Hurley, WI and Mellen, WI. Between 1886 and 1965, 71 million tons of iron was taken from several shaft mines, the deepest running almost a mile below Earth's surface.

The mines were all shut down by 1965, due to the

advent of cheaper-to-operate open pits in Minnesota’s Mesabi Iron Range,

Michigan's Marquette Iron Range, and competition from inexpensive foreign ores.

Now the Penokee-Gogebic Range, after a nearly 40-year lull in interest, is once

again on the radar screen of mining interests. Two companies, LaPointe Mining

Co. of Duluth, MN and RGGS Land and Minerals, Ltd. of Houston, TX, own nearly

all of the mineral rights in the range. Together they control 22,500 acres

along a stretch of land from Anderson, MI to about six miles west of Mellen,

with RGGS holding a 62 per cent share. A third interest, the Vilas Trust, holds

about 5 per cent of the land.

The mining companies would like to develop an entire steelmaking industry to go with the mine, said Meineke. This would include the building of a taconite plant and small steel mill. Congdon and Meineke have stated that the mine could be in production for 50 to 100 years and create hundreds of jobs.

Additional infrastructure such as roads, railroads and a power plant would need to be included in the plan. The companies are currently searching for an investor to put up the estimated $1 billion in initial costs, according to Ray Lahti, an independent consultant who presented information on the mine in Ashland, WI to the Sigurd Olson Environmental Institute.

Filing for a permit to mine with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources would not take place for at least 3 to 5 years, according to Congdon.

The reason a large-scale open pit mine has never been attempted in the area has to do with the features of the iron deposit. The deposit lies at a 70 degree angle and is buried an average of 350 feet from the surface. The ore is only about 20 per cent iron, but is magnetite, which can be crushed and extracted with high-powered magnets. According to presentations by mining company officials, the mine would stretch in segments over 21 miles, descend 600 to 900 feet and be about 1200 feet wide. The Bad River, which passes across the ore body in Mellen, would be spared by a 1000 foot buffer on each side of the river. Overall, some 1.1 to 2 billion tons of iron would be removed from the mines. This volume represents 10 to 20 per cent of the known iron ore deposits in the United States, said Congdon and Meineke.

Taconite Outcrop Along Hwy.13, South of Mellen, WI Photo Anna Hochhalter

The Penokee-Gogebic Range has recently been identified by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) as having a high potential for undiscovered copper and nickel deposits. If iron mining were to occur, copper could be produced as a by-product, and pose risks inherent to all metallic sulfide ore mining.

Mining in the Penokee-Gogebic Range could pose a significant threat to the environment on which surrounding communities depend for their sustenance. Aside from large-scale aesthetic impacts to the landscape, currently-intact forests would become highly fragmented, while increased runoff and potential heavy metal or acid contamination from tailings piles could dramatically alter the health of river systems. Heavy machinery and industry would produce hydrocarbon emissions and ore dust that contribute to deteriorating air quality and global climate change.

The area is at the headwaters of the Bad River, the largest Wisconsin watershed draining into Lake Superior. The Bad River is home to 72 species of rare and endangered plants and animals, according to the Nature Conservancy.

Most significantly, changing water levels and pollutants entering the river could impact Wild Rice beds growing at the river’s mouth. Mahnoomin is important to the economy and life ways of the Bad River Band of Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) people. In addition, the tourism-based economies of lakeside communities such as Bayfield, Washburn, and Ashland could be negatively impacted, as contaminants from mining could easily reach Lake Superior.

Mining executives have said that they are sensitive to environmental concerns, and point to new technologies that they say pollute less. “[W]hat we're proposing is not Gary, Indiana,” said Meineke. But some residents worry that the image of the area as a North Wood’s paradise could be forever marred by large open-pit mines.

Even with the best technology, environmental consequences might outweigh the short-term economic benefits of such a mine.

Written by Brian Clements & Carl Sack, March 2008