Back Read this article on line - Thank you, Sierra Club

Pig Confinement Technology Risks Deadly Fires

“They were really squealing,” a worker told a TV reporter last July after a fire destroyed a hog confinement north of Wichita, Kansas. The barn, which the industry calls a nursery unit, contained 2500 young pigs, and none survived. In 2011 and 2012 there were at least 22 hog barn fires in the U.S. and Canada that killed about 28,000 pigs. During that period five other fireskilled 300 dairy cows, 7,000 turkeys and over a half million laying hens.

Many of the news stories cite the intensity of these fires and how rapidly they spread. Typically the buildings are completely engulfed by the time the fire fighters arrive, and few animals are rescued. There may be other such fires that go unreported, but it would be hard to miss, even in rural areas, a red-orange horizon in the night or a large plume of smoke during the day.

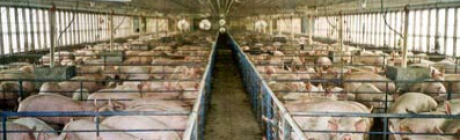

Barn fires have occurred since the early days of animal agriculture, but the industrialization of animal husbandry in the past several decades has greatly expanded the scale of this tragedy. Huge numbers of pigs, dairy cows and poultry have been confined in what are called concentrated animal feeding operations or CAFOs. The underlying technology, as championed by agricultural engineers, is called intensive confinement.

The scale of destruction from these fires is a direct consequence of intensive confinement technology. The most obvious problem is the cramming of so many animals into the buildings in the first place. Since they are being fed rich diets to speed growth, a huge amount of manure is produced. All this manure sitting around generates what is known as manure gas, a noxious mixture of hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, carbon dioxide, methane and odorous organic compounds.

In “deep pit” designs where the manure percolates under the animals for six months or more before being pumped out, the buildup of highly flammable methane is a known explosion hazard. It is unclear why these fires erupt and spread so rapidly in other confinements where the manure is removed more regularly. It is less a mystery why the fires become so intense. Canada’s Farm Animal Councilspublished a fact sheet for first responders1noting that “pigs are highly flammable.”

Hydrogen sulfide gas is highly toxic to both humans and animals, and ammonia is a serious irritant, so it is essential to ventilate the buildings. Carbon dioxide is not normally a toxic gas, but so many animals are housed in these barns that the animals will suffocate for lack of oxygen if the barns are not naturally or mechanically ventilated. This ventilation means that, once a fire gets started, it enjoys ideal conditions to intensify.

These operations are so highly automated that there’s usually no one around when the fire breaks out. When known, the cause is almost always related to sparks from defective wiring, instruments or machinery in the building. Few animals can be saved because the buildings are not designed for them to easily escape, even if there was time. Sows are trapped in tight cages called gestation or farrowing crates, and terrified animals are very hard to handle. Media stories frequently report that firefighters had to use tankers to haul in water from distant ponds or streams to fight the fires. That’s because hog confinements must be located well beyond the reach of municipal fire hydrants because of strong odors.

Beside fires and explosions, there are many other built-in problems with intensive confinement technology. These are: the heavy use of antibiotics and the evolution of antibiotic resistant bacteria, persistent viral disease among the closely confined animals, heat stress, respiratory disease among workers, lowered property values for neighbors and extensive air and water pollution.

So, how can this go on? The industrialization of meat production has resulted in a strict standardization of pork products and a commodity pricing structure that continually haunts operators of CAFOs and penalizes them for any deviation that might raise costs. Apparently, decent people continue to participate in this system because the industry is able to almost completely objectify the animals, and consumers don’t really know what is going on. If CAFOs were classified as the factories they really are, instead of “farms,” they probably would not be allowed to exist.

The intensive confinement of food animals is a dumb technology devised by otherwise smart people, who are themselves intensively confined within an aging paradigm. After WWII, America’s politicians and industrialists decided that we must become the low cost producer to “feed the world.” It was a notion built upon cheap energy, the invention of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, and the renewed exploitation of America’s vast prairies and grasslands with their untapped aquifers. More money could be made if we ran the grain through animals and sold meat, than if we sold the grain directly. The USDA dutifully parroted the livestock industry and promoted what we now know as the modern American meat diet.

But millions of heart attacks later, and after the release of billions of tons of greenhouse gases, the hot-and-dry line is moving up from the Southwest. The aquifers are thinning, and diesel fuel is no longer cheap. Our new climate will become increasingly incompatible with the cramming of thousands of hapless animals into small spaces, and with the production of vast amounts of grain to feed them.

Anyway, the current system is inherently cruel, utterly unnatural and scientifically misconceived. I don’t want any part of it, so I eat less meat and buy free range from farmers I know.